What do you think when you imagine being unwell at altitude? Frostbitten toes dropping off, splitting headaches, and blood leaking from places it shouldn’t be are what most people would say. It sounds gruesome, doesn’t it? The fear of altitude sickness understandably puts the fear of God in both seasoned and beginner mountaineers, and while it can be extremely dangerous, it helps if you know what to expect at high altitude.

What to expect at high altitudes and how to stay safe

I’ll be the first to admit that even though I was typically unprepared the first time I ventured to extreme altitudes, I still spent hours doom-scrolling the NHS pages on pulmonary and cerebral edemas. Since my first trip above 5000 m, I’ve crossed well beyond that threshold two more times, but it wasn’t until I climbed Huayna Potosi in Bolivia that I questioned what was happening to my body and, crucially, why other people fared much worse.

It’s for this reason that I’ve dug deep, hyper-focused, and scoured the internet for information to answer my burning questions, such as, Why do some people suffer so greatly? What can I do to protect myself? Where are the dangers of altitude sickness at their greatest? and much more.

If you’re planning a trip to the roof of the world, or even if you’re just curious about what to expect at high altitude, I hope this article scratches this itch.

What is high altitude?

This is actually a little more difficult to answer than it may seem because, essentially, it’s relative to the person who is experiencing it. For someone like myself who grew up in England, you could probably argue that anything above 1000m is high altitude, and even at this height, I would experience very slight effects of altitude. However, if you’re a Sherpa, you could be completely accustomed to 3500m of altitude on a daily basis.

For the sake of simplicity, however, we tend to group altitude into three categories, as I’ll explain below.

- High altitude = 1,500–3,500 metres (4,900–11,500 ft)

- Very high altitude = 3,500–5,500 metres (11,500–18,000 ft)

- Extreme altitude is above 5,500 metres (18,000 ft).

At each of these levels, an individual can experience different effects depending on whether they have acclimatised to the appropriate level. At the lower levels, it can be as slight as a tiny change in your vision, but at extreme altitudes and above, the risks are a lot greater and the symptoms much more noticeable.

How is altitude different from sea level?

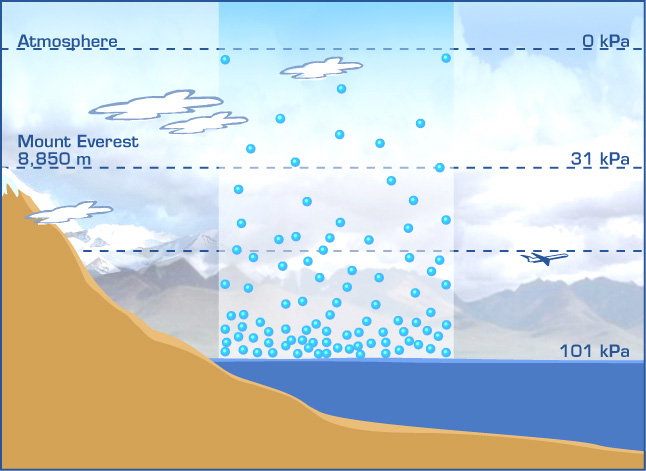

There is a common misconception that at altitude there is less oxygen to breathe in the air. This isn’t the case, and it is a little more nuanced than that. As any budding mountaineer or trekker moves higher and higher in altitude, they experience a change in air pressure compared to sea level.

The composition of molecules in the air stays exactly the same, with nitrogen (79.04%) and oxygen (20.93%) making up the majority of each breath we take. However, at altitude, the molecules are further apart because there is less pressure in the air to push them together.

Put simply, this results in you being able to breathe less oxygen per lungful as the molecules are all spread out. At the summit of Everest, there are a third of the useful oxygen molecules that you’re breathing per lung; at Everest Basecamp, that number is more like half.

What is altitude sickness?

The name “altitude sickness” is actually a bit misleading because it implies that there is only one condition. In reality, altitude sickness is an umbrella of three different conditions that are most commonly triggered when unfortunate adventurers ascend to altitudes that they aren’t used to.

The biggest danger in altitude sickness is that it is rare for someone to suffer from only one of the diseases. If you’re taken to the hospital for HAPE, you will also be treated for HACE because the mechanisms and causes are the same and the surface-level symptoms often overlap.

These combinations of illnesses can be fatal in the worst extremes, and the internet is full of stories of this nature. But that isn’t the purpose of this post. I’m not trying to scare you like I did myself before my Nepal trip; this is crucial to your understanding of the illness.

[modula id=”206″]

Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS)

Acute Mountain Sickness, or AMS, is the most common of the three and normally starts to occur at altitudes of 2500 m+ in unacclimatized individuals, with a usual delay of 4–12 h after arrival at a new altitude.

A leading symptom of AMS is a persistent dull headache above the eyes and at the back of the head, but other common symptoms are a loss of appetite, nausea, fatigue, lethargy, and insomnia. Almost everyone I’ve met on the mountain has had at least one of these symptoms; on their own, they’re nothing to be too concerned about. But if they start to combine, you need to descend.

From my experience, the best way to explain the feeling of mild AMS is to imagine someone who went out last night and drank 15 pints. It’s now 3 p.m. the next day, and they look and feel pretty terrible. If you ascend from 1500m to 4500m without an acclimatisation day, you’re likely to feel like this.

High-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE)

HAPE is more likely to appear at higher altitudes than AMS, usually above 4500m. An edema is a word used to describe swelling from trapped fluid; in this case, this would be fluid within the lungs.

Trapped fluid in the lungs is, unsurprisingly, really dangerous. It becomes so hazardous because the sacs within the lungs that would ordinarily absorb oxygen and CO2 fill with fluid. So you take in significantly less oxygen with each breath while also being at an altitude where there are a lot fewer oxygen molecules per lungful of air. This results in people with the condition taking lots of short, sharp breaths and their heart rate shooting up; by all intents and purposes, it looks as if they are suffering from pneumonia.

High-altitude cerebral edema (HACE)

HACE, like HAPE, is most common above 4500m. Like HAPE, it is caused by a buildup of fluid causing swelling, but in this case it is within the brain.

If you’re watching someone who is suffering from HACE, they may look like they’re in a drunken stupor. They will often have something called ataxia, which causes them to stagger around like they’re the best man at a wedding while holding onto anything they can for support.

In some cases, they can also get extremely warm and, as a result, strip their clothes off to cool down. When you’re above the highest peaks in Europe and it’s -10 °C outside, this also increases the risk of frostbite and hypothermia. One of the easiest ways to tell if someone is developing HACE is through their behaviour; if they’re not behaving like a rational person would at altitude, it’s possible that it has started to onset.

However, it is also possible for someone to be excessively sleepy, which in extreme cases can cause people to slip into a coma (less of the belligerent, overly intoxicated reveller and more of the sleepy drunk person).

I know HAPE sounds terrifying, but you should know how rare it is. A 2021 study calculated that 0.5% to 1% of people visiting high altitudes were affected by HAPE.

[modula id=”202″]

Where are the dangers of altitude sickness at their greatest?

This is a relative question, depending on the individual and how acclimatised they are. However, a general rule of thumb is that the higher you go, the greater the risks. Although I previously said there are 3 categories of altitude, in reality there is a 4th.

Above 8000m has been affectionately dubbed “the death zone.” This might sound a bit dramatic, but it’s actually factual. At this height, it is impossible to sustain life permanently; sleeping becomes nearly impossible, and digestion of food is incredibly difficult. This is why the highest camp on all the world’s tallest peaks is below this altitude.

For the average person who isn’t climbing the world’s tallest peaks, though, the true danger zone is most likely to be around 4500m. This is because it is when the risks of developing HAPE and HACE start to elevate, which are the riskiest of the three main altitude sickness conditions.

What can I do to treat altitude sickness?

So how exactly do you treat the onset of altitude sickness? There are a few natural remedies, depending on where you are in the world, and some pharmaceuticals that are universal. But I really want to stress that the best way to treat altitude sickness is simply to descend.

The natural remedies

So this depends on where you are in the world, and the science behind them is shaky at best. But from my personal experience, both of these did alleviate at least some of the symptoms of AMS.

South America

In the Andean regions of South America (Bolivia, Peru, Northern Argentina, and Chile), the Coca plant grows naturally. While it is the main component of cocaine and, as a result, has suffered bad press worldwide, it is sacred to the people native to the area. More to the point, it has been used for thousands of years to alleviate the symptoms of altitude sickness.

Scientists are divided on whether consuming the leaves helps with altitude sickness, but there has been some promising research in recent years. One study conducted in Cajamarca, Peru, at an altitude of 2500m concluded that chewing the leaves induces biochemical changes that enhance physical performance at high altitudes.

Himalayas

When I completed the Annapurna circuit and my guide noticed that I was struggling, he advised me to have garlic soup at every meal. This sounds utterly ridiculous; how can something so widely available assist with altitude sickness? This is exactly what I thought, but as I had no appetite and needed to eat, soup seemed like the best option.

To my surprise, I noticed an almost immediate difference, and while my guide was unable to explain why it had this effect, I’ve since done some research that helps to explain this a little. This study conducted on rats suggests that garlic influences blood flow within the brain and therefore can help with preventing some high-altitude illnesses.

Pharmaceutical remedies

There are a few different pharmaceutical remedies that are used worldwide, but the most common is something called Diamox (Acetazolamide). This is readily available and cheap anywhere worldwide where you’re likely to be at altitude, although it tends to be a bit pricey in Europe and North America.

There is a wealth of proven science behind this, so prioritising this over the natural remedies above should always be your choice. It works by combating oxidative stress at altitude; in simple terms, it improves the ability of red blood cells to carry oxygen through the body. This helps to improve your performance at altitude, alleviate some symptoms of AMS (lethargy, headaches), and can also serve as a treatment for pulmonary edema (HAPE).

Why does altitude affect everyone differently?

When I completed the Annapurna Circuit and was on the final push to the Thorung La Pass (5416m), I was struggling with my energy levels and had a slight headache, which was to be expected. But I will never forget the sight of a woman in another group who was crying, staggering slightly, and having to be almost carried up the last 100 metres by her guide and partner. She wasn’t unfit; on the contrary, she looked more athletic than me, so why was she affected so badly?

This is a story that has been compounded by almost everyone I have met who has ventured to extreme altitudes. The effects and symptoms appear to vary wildly depending on each person. And the fitness of the individual seems to have little or no bearing on what symptoms you will suffer.

There is some evidence that suggests that people who suffer the worst symptoms of AMS have a low tolerance to hypoxia (lower levels of oxygen in their tissues).

So just as some people, as a result of genetics, are not the best at football or singing, some people just struggle with the reduction of oxygen in their systems. Those who have disorders that affect how much oxygen can be carried by their blood are also more likely to suffer from symptoms of altitude sickness.

Some final tips on avoiding altitude sickness

There is a reason why the average ascent of Everest takes 4-5 weeks; acclimatisation is key. You need to spend more time at altitude to allow your body ample time to adjust to the change in air pressure.

We have a tendency as tourist trekkers to try and pack everything into as small of a timeframe as possible, usually to meet our limit of annual leave. But there is no better way to limit the effects that you will feel from altitude than to slow down and spend time at each altitude level before progressing to the next.

A rule of thumb is that you should have one acclimatisation day for each 1000m of altitude that you gain. On this day, you should ideally trek to a higher altitude, then return to your accommodation to sleep before progressing further up the mountain the next day.

With this in mind, always pick a trekking or climbing itinerary that’s a bit slower; it’ll also give you more time to soak in the incredible views and landscapes before you.